My 4:30 a.m. wake-ups seem to be a thing of the past. Now I'm rising in the usual 5:30-6:00 range. This still gives me time to occasionally catch a quality (by my standards) movie or TV show that have been lost to time but deserve a quick mention -- the same way I'll be treated after I'm gone. Alphabetically:

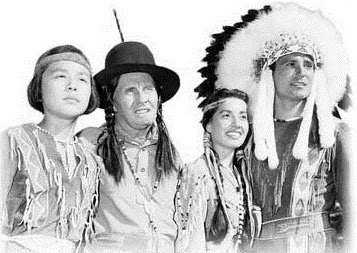

BRAVE EAGLE (1956): A short-lived TV series told from the perspective of the Native Americans. In the episode titled "Moonfire", white settler Penny Pattifore is rescued by Chief Brave Eagle from the clutches of an opposing tribe. Initially frightened, Penny, given the honorary tribal name Moonfire, decides she'd like to go native with Brave Eagle and company. She's rebuffed by Smokey, the tribe's token halfbreed, which sounds a little hypocritical if you ask me. Penny decides her fate by sitting atop a "vision rock" (no mention of psilocybin being involved). Her uncle, Col. Matthews, is ready to kill her new friends in order to bring her back to "civilization". Luckily for them, Penny decides cultural appropriation isn't cool after all. She wouldn't have looked good in a headdress anyway.

One of the dozens of 1950s TV Westerns, Brave Eagle deserves to be commended for making the usual bad guys into the heroes. And by "heroes", I mean knowing their place. Brave Eagle goes so far as to provide safe passage for white people who, of course, are stealing his people's land. That's the kind of redskin we like!

Where it doesn't differ is that almost all of the lead characters are played by whites. Keith Larsen, as Brave Eagle, looks as Native American as Errol Flynn. I mean, he doesn't even wear that stupid red make-up you see in these things.

But what puts Brave Eagle into whacko territory is that his sidekick Smokey is played by Bert Wheeler of Wheeler & Woosley fame. And despite being the only actor wearing "Injun" make-up, Wheeler delivers his lines in his usual wisecracking style, as if Smokey's white father had been a pre-vaudeville comedian. Again, the halfbreed hypocrisy is stunning.

Brave Eagle's contradictions put today's woke viewers in a bind. Respecting Native American culture, heritage, and knowledge: good! Not respecting it enough to cast a real Native American in the lead: ugh!

BONUS POINTS: When informed that his niece Patti has gone to the vision rock, Col. Matthews simply accepts the explanation rather than saying, as any 19th-century American soldier would, "What the fuck is a vision rock?!"

CHLOE, LOVE IS CALLING YOU (1934): Mandy, a/k/a Mammy, returns to her home in the Florida Everglades seeking revenge on Col. Gordon, the white man she believes lynched her husband 17 years earlier. Accompanying Mandy is her daughter Chloe, and her assistant Jim, both of whom had white fathers. Chole resists Jim's amorous moves while finding herself attracted to the white Reed Howe, who manages Col. Reed's turpentine factory (what a man!). Chloe soon discovers that she's actually Col. Gordon's daughter and was kidnapped by Mandy as a baby. She's now free to marry the white guy -- yay for the honky girl! -- if she isn't sacrificed in a voodoo ceremony first.

Wowwee! Chloe, Love is Calling You has it all -- racial politics, interracial love, black stereotypes, voodoo, and authentic animal abuse. A mainstream studio release this is not.

Yet for all its, shall we say, debatable social viewpoints, the movie, at least in the beginning, makes Mandy sympathetic. Can you blame her for wanting revenge on the guy who allegedly lynched her husband on "the death tree"? That alone sets it apart from other movies of its time.

But once we learn that Col. Gordon is innocent of the charge, and that Chloe is actually 100% pure-as-Ivory Snow white, it regains its footing as a weird, racist, low budget indie exploitation melodrama that will never be run in any film studies class today.

Chloe, Love is Calling You was the last stop for lead actress Olive Borden, whose bad attitude, drinking habits, and difficulty transitioning to sound saw her fall from $1,500-per-week, 1920s stardom to alcoholic scrubwoman at a skid row homeless shelter in downtown L.A. That's Hollywood!

MEET THE MAYOR (1932): Imagine Forrest Gump, only with a slightly higher IQ and never getting laid. That's elevator operator Spencer Brown. But he's smart enough to help best pal Harry Bayliss invent a home recording device which eventually gets the goods on the honest mayor's crooked rival. Just not smart enough to realize the girl he crushes on loves Harry. What a dolt.

Likely realizing his suave stage persona didn't play outside of the New York stage, Frank Fay's characterization of the smalltown Spencer Brown -- a cross between Harold Lloyd and Harry Langdon -- was a desperate attempt to achieve the movie stardom that had eluded him. His low-key performance is occasionally affecting, particularly when he forces the mayor's rival to drop out of the race. Yet none of the major studios would release the Fay-financed Meet the Mayor, despite it being no worse than many movies of its time.

Perhaps it was because Frank Fay -- the first stand-up comic --

wasn't boffo box office. On the other hand, being a raging anti-Semitic racist

who counted Franco supporters, the Ku Klux Klan, and the American Nazi Party as

his best only friends couldn't have helped.

The two-bit outfit that finally released Meet the Mayor in 1938 -- six years after its production! -- must have had second thoughts as well, seeing that Fay's name on the opening credits is about the size of the copyright notice. That's what happens when your star would have been comfortable in a movie called Meet the Fuehrer.

BONUS POINTS: Meet the Mayor is the earliest movie I know of that uses the phrase "Looking out for number one" and the slang "coffin nails" for cigarettes. Do I win a prize?

PAROLE, INC. (1948): Special agent Richard Hendricks goes undercover to find out why the locale parole board keeps freeing dangerous prisoners. He infiltrates a posse of low-rent gangsters, who seem to do nothing but play cards at a diner all day. (Maybe if they committed a few more crimes, they'd get somewhere.) Hendricks soon discovers their puppet master -- a lawyer -- is paying off the board members. That's one way of having a constant stream of clients returning to you, even if it does cost a few bucks off the top.

PAROLE, INC. (1948): Special agent Richard Hendricks goes undercover to find out why the locale parole board keeps freeing dangerous prisoners. He infiltrates a posse of low-rent gangsters, who seem to do nothing but play cards at a diner all day. (Maybe if they committed a few more crimes, they'd get somewhere.) Hendricks soon discovers their puppet master -- a lawyer -- is paying off the board members. That's one way of having a constant stream of clients returning to you, even if it does cost a few bucks off the top.Low budget B's like Parole, Inc. did a better job of showing the seedy criminal underworld than the A's. Actors like Bogart, Robinson, and Cagney always seem like they're living the good life. You can tell just by looking at the crew in Parole, Inc. that they reek of cheap cologne, Lucky Strikes, and stale Ballantine Ale. There's nothing romantic or exciting about these yeggs and their lifestyle.

Everybody is reminiscent of actors that the producers couldn't afford. Michael O'Shea, as Hendricks, is a cut-rate Dan Duryea. Turhan Bey, the lawyer, sounds like George Sanders despite being of Austrian/Turkish/Czech heritage. His sweetie, Evelyn Ankers, is vaguely reminiscent of Joan Crawford, though less glitter and more gutter.

Between the cast, cheap sets, and not-so-great dialogue (crooked parole board member facing cops with tear gas: "They've got gas and I've got sinus trouble!"), Parole, Inc. is a more accurate look at low-rent criminals than anything Warner Brothers made. Just not as good.

BONUS POINTS: Michael O'Shea speaking the phrase "punchboard racket" with a straight face. Also, one of only four movies credited as "An Orbit Production."

THE STUDIO MURDER MYSTERY (1929): Who killed leading man Richard Hardell? Was it his wife Blanche, who was sick of his tomcatting? Hardell's sidepiece Helen MacDonald, who learns he will never leave Blanche? Helen's brother Ted or her father, both of whom hated Hardell? Hardell's director Rupert Borka, who suspected Hardell of fooling around with his wife?

Brother, if you can't figure it out by the end of the first reel, you have no right to watch any mystery. No matter. Movies like The Studio Murder Mystery are strictly for pleasure. Not only do we see the Paramount Pictures soundstages when they're not in use, we also glimpse a recreation of how silent movies were still being shot. Too, many scenes take place outside the Paramount gate, where the actors' breaths are visible in the nighttime scene. L.A. must have been mighty chilly in early '29.

Unlike other early talkies, The Studio Murder Mystery showcases actors delivering their lines in normal tones rather... than... very... slowly. Fredric March (Hardell), Warner Oland (Borka), Eugene Pallette (Detective Dirk), and Neil Hamilton (wiseacre gagman Tony White) enunciate while still sounding like real people -- if real people had a script at the ready. Although it's still impossible not to hear Oland without thinking of his soon-to-be career-changing move as Charlie Chan. (Why does a Swedish-born actor playing an Eastern European sound Asian?)

At 62 minutes, the fast-paced The Studio Murder Mystery never has a chance to be dull. What it lacks in genuine mystery it more than makes up for with entertainment. But it kind of makes you wonder what Fredric March thought being killed off ten minutes after the opening credits.

BONUS POINTS: Studying the reactions of Florence Eldridge as Hardell's two-timed wife, since in real life, she had to put up with the same sexual shenanigans from her husband -- none other than Fredric March! Talk about method acting.

****************

2 comments:

Thanks for another lively read, Kevin!

I was wondering when you were going to get around to Frank Fay, ghastly human being that he was- about as welcome as haemorrhoids in a bobsled team.

Fay had worked for Warner Bros since 1929 but the shine was off by 1932, although they agreed to distribute the film they dropped it pretty quickly.

The reemergence in 1938 when the film was sold States Rights had new titles that Warners agreed to do, with Fay's name in the smallest possible type, as you say. Another interesting point is that in this, as far as I know only surviving version, the copyright is not only unassigned, its wrong- it reads 1927. This must be deliberate, perhaps another way to nudge the film out of any credible copyright several years before it should have.

Although much is unclear, what is clear is how much everyone hated Frank Fay. And I'm with them on that!

Hi Gary, thanks for leaving a comment. It seems that the only difference between Frank Fay and Mel Gibson is that Mel made a lot of money for studios in his prime.

Post a Comment