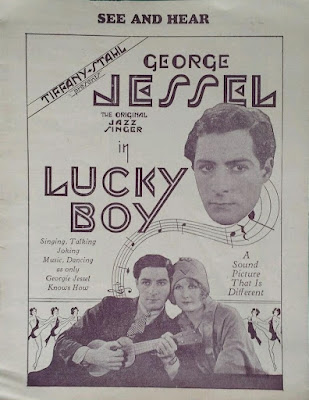

Credit -- make that discredit -- lies with scriptwriter/ star George Jessel, one of the most inexplicable celebrities of the 20th century. If Lucky Boy is any indication, the 1928 version of Jessel was little different from the tedious talk-show nudge of four decades later, viz: A personality similar to a dead flounder; an endless supply of hackneyed jokes and mawkish songs delivered in a mumbling, nasal voice bordering on the near-incomprehensible; forever confusing sentiment with sentimentality; and sporting a hairpiece that wouldn't fool a blindfolded mite.

Originally titled The Ghetto until a last-minute change, Lucky Boy features its star playing someone named Georgie Jessel. And if that first name sounds adolescent, it's no accident. In the movie's early scenes, Jessel plays the teenage version of himself swearing to run away from home -- when the actor himself was 30!

Poverty row studio Tiffany-Stahl promoted George Jessel as "The Original Jazz Singer". It was a reminder that he had been the star of the Broadway play of the same name, only to lose the movie version (and his place in film history) to his frenemy Al Jolson in a salary dispute with Warner Brothers. Whether called The Ghetto or Lucky Boy, the title of the short story on which this cinematic consolation prize was based is probably more appropriate: "The Schlemiel".

BONUS POINTS: The only legitimate laughs are provided when Jessel makes a few pointed jokes regarding Henry Ford's antisemitism.

WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD! (1931): Viennese-born actor Paul Morgan arrives from Germany to report via shortwave radio on his experiences in Hollywood. After a German expatriate shows him around the city, Morgan literally parachutes into the MGM studio, where he meets Buster Keaton, John Gilbert, Joan Crawford, Adolphe Menjou, and Leo the Lion. In the evening, he attends a movie premiere where even more Metro actors appear.

Yeesh, that's it? Now picture the whole thing in German without subtitles, and in a washed-out print. That's Wir Schalten Um Auf Hollywood! (in English, We're Switching to Hollywood!), made for release exclusively in Germany, one of Hollywood's biggest foreign markets. And brother, they can have it.

Strictly for obscurity fanatics, Wir Schalten... features production numbers from the never-released 1930 Metro musical revue The March of Time. Two of the numbers are obviously cut from what seems to be the sole surviving print of Wir Schalten..., although we're blessed to see a recreation of a turn-of-the-century vaudeville routine featuring people tapdancing in horse costumes. The picture also gives us the opportunity to hear Joan Crawford awkwardly attempting to speak German. Adolphe Menjou, though, is utterly fluent in a weird movie-within-a-movie where he's eventually shot by Paul Morgan, climbs a ladder to Heaven, then enters a cinema where he orders the film rewound so that he lives.

Other than Menjou's commendable German delivery, the movie's highlight is Buster Keaton ignoring Paul Morgan in the Metro commissary. Likely shot in one take, a bored-looking Keaton gets more laughs fooling around with cutlery than most comedians with a closet full of props. He returns at the climax dressed as a caveman to knock Morgan unconscious with a club. Wir Schalten Um Auf Hollywood! will make you yearn for the same fate.

BONUS POINTS: Sergei Eisenstein can be seen at the climactic movie premiere. Russian filmmaker at a Hollywood premiere in a German movie -- gee, it looks like we can all get along!

STREET OF CHANCE (1942): Before griping about your day, consider the plight of Frank Thompson. After getting conked on the head by a piece of falling debris, Frank gradually learns he had been living as someone named Danny Nearing for the last year. As Nearing, he was having an affair with a dame named Ruth Dillon despite him being happily married to another woman. Confused yet? So is he -- especially when a silent, tough guy gets on his trail. Oh, and I almost forgot: Frank is wanted for a murder he can't remember! And the only witness who can clear him is a bedridden old crone who can't speak. Like I said, no complaints about your day.

Based on a story by Cornell Woolrich, Street of Chance's main characters all reflect Frank Thompson, in that none of them are who they appear to be. Ruth Dillon is just a housekeeper -- until she isn't. Frank's hulking nemesis Joe Marruci appears to be out to kill him -- except he doesn't. The two survivors of the murder victim are the obvious suspects -- up to a point.

Director Jack Hively seems to have wanted to jazz up what would have been an ordinary B-mystery. His use of lighting (and darkness) is effective, as are the impressive crane shots that literally elevate the movie's look. Still, there's never a minute during Street of Chance when you aren't cognizant that the movie makes absolutely no sense, is overflowing with handy coincidences, and sports more loose ends than a welcome mat that's been caught in a tornado. Maybe that's why it's so entertaining.

BONUS POINTS: The grandly-named Adeline DeWalt Reynolds, who plays the elderly mute, entered the movie business at age 78, two years before Street of Chance's production, and continued until her death in 1960. See all you aspiring actors, there's hope for you yet!

*************

.jpg)

1 comment:

I never realized early Hollywood was quiet so bizarre.....

Post a Comment