Strictly by coincidence, this Early Show has two "bringing the dead back to life" movies, and two TV shows from the early 1960s. If you've seen any of these, the next drink's on me. On a Zoom call, I mean.

SIX HOURS TO LIVE (1932): Paul Onslow, an ambassador of Sylvaria, has been assassinated by an unknown person. Good news: The police commissioner has a friend who's invented a machine that can bring the dead back to life. Bad news: They can stay alive only six hours. (You'd think he'd have worked a little harder on fixing that glitch.) Onslow will use that time to have dinner, explain to the woman who loves him that he's no longer the marrying kind, find the guy who killed him, and remind the police commissioner that death is scary only in your mind. I'd have dropped a couple of tabs of acid, but to each his own.

Sci-fi, horror, and politics were hot stuff in the early '30s movies. Six Hours to Live manages to combine all three genres, along with a dash of romance. Onslow is the only representative who refuses to sign a pact involving international finance, believing that it's a cover for the major governments to make out like bandits while their citizens get nothing. He isn't wrong -- that's why someone at the table wants him out of the way in order for a substitute to vote yea. Otherwise, the pact is null and void, as Onslow will be in a few minutes. Once revived, he has a new appreciation for life, taking a moment to help a streetwalker (money only!) and a little flower girl (ditto). Onslow doesn't even kill his assassin, preferring that the guy suffers "a living death". Today, that's known as, well, life as we know it.

Six Hours to Live's political angle was typical for its time, being a mildly progressive subplot that drives the story. Warner Baxter makes Onslow the rare rich guy in a silk cape who's on the side of the little man. (The cape also gives a Dracula-vibe when he's closing in on his killer.) Nor does he overdo his (second) death scene. Wilting like a flower, Baxter rests alongside a tree as a beatific gaze passes over his eyes as the end comes. Director William Dieterle (Syncopation) provides style perfectly fitting all the genres the movie covers -- the life-revival scene could fit in any horror movie of its time. It's just too bad that, as usual, Six Hours to Live's print on YouTube is bleary and over-pixilated. The Musuem of Modern Art possesses a restored version, but you have to be, you know, a scholar to access it. Ergo, I advise you to skip Six Hours to Live as it appears online and wait for someone at MOMA to drop dead for six hours so you can sneak in and see their print. (Kidding, MOMA, kidding!)

BONUS POINTS: Two years earlier, co-stars John Boles and Marilyn Harris were in Frankenstein, as Victor Moritz and the little girl who gets thrown in the lake respectively (if not respectfully).

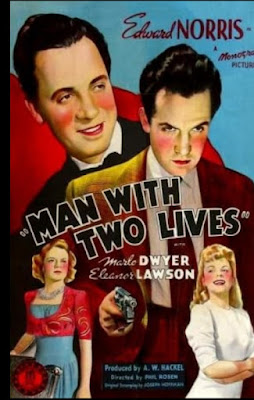

By the 1940s, only a B-movie outfit like Monogram would try pulling off a sci-fi/ gangster hybrid like Man with Two Lives. And gosh darn it, the thing works -- up to a point. One-time A-list supporting actor Edward Norris plays the title role -- or roles -- convincingly; his transformation into a cold-blooded gangster is something of a shock, as is his blunt romancing of Panino's trashy moll Helen, along with his growing hatred of his loving family and fiancée Louise. Even Panino's gang is scared of him. Yet you can see something of the good Phillip underneath the monster from time to time, giving his character a complexity not usually seen in B's. You actually start feeling sorry for him -- here's a guy through, no fault of his own, is on a very obvious self-destructive path, thanks to an ill-considered wish from his loving father and twisted brilliance of a scientist...

Which is probably why at the very end, Man with Two Lives goes kablooey when the story turns out to be a nightmare suffered by Phillip during a four-day coma following the accident. I hate when that happens, especially in a movie as good as this. Had Man with Two Lives (couldn't Monogram afford a "The" in the title?) been a pre-code from a decade earlier, Phillip would have been shot by a cop as he was here, but too damn bad about how it wasn't his fault. His father and the scientist would be condemned to a lifetime of guilt; his fiancée would never know a day's happiness from then on. Doesn't that sound like a better picture?

BONUS POINTS: Phil Rosen, the director of Man with Two Lives, showed how powerful a gloomy climax could be with his previously-discussed Monogram pre-code The Phantom Broadcast.

DR. KILDARE (UNAIRED PILOT) (1960): It isn't unusual for a TV series to undergo cast

changes before its premiere. Dr. Kildare went a step further to change the lead actor and concept. For the pilot, Lew Ayres was brought back to recreate his starring role from MGM's nine Kildare movies from 1938 to 1942 (and 1950 radio series). No longer a young intern, he's now chief diagnostician at Blair General Hospital. And as Dr. Gillespie mentored him decades earlier, so Kildare mentors the young intern Dr. Grayson. The circle of life and all that.

Lionel Barrymore, the original Gillespie, was six years dead but not forgotten, as his portrait hangs in Kildare's office. Ayres even quotes a line of dialogue Barrymore spoke in one of the movies (a reference to a "mentally retarded ringtail baboon" wouldn't make the cut today). The story itself -- Kildare wanting to keep Dr. Grayson at the hospital rather than allowing him to go into private practice -- is a remake of one of the early Kildare movies. (Don't ask me which; they all blend together in my memory.) Kildare goes behind Grayson's back to upset his plans, causing a brief rift between the two before amends are made during a run-up to brain surgery, no doubt a common event in busy hospitals during the overnight shift.

BONUS POINTS: The Kildare pilot was directed by John Newland, the director and host of One Step Beyond. Olan Soule, one of the most familiar character actors in TV history, plays a doctor. Do a Google Image search; if you're of a certain age, you'll automatically say, Oh, that guy!

Zone, One Step Beyond was my favorite spooky show during childhood. The difference between the two was that One Step Beyond was based upon true stories -- maybe. As host John Newland explained at the end of the episodes, nobody could prove or disprove their veracity. For a gullible eight year-old, that was good enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment